Ravenna is without any doubt one of the most important cities of the Italian, European and Mediterranean Early Middle Ages. However, despite everything, including its rich Unesco heritage, which is well-known and celebrated worldwide, the city has never had that fame that characterized many other Italian destinations.

Nonetheless, Ravenna played a fundamental role during those centuries (5th-6th century AD) that marked the beginning of the Middle Ages in Europe, affecting as a consequence the modern and contemporary balances.

Thanks to the monuments and the evidences that are still existing and visible, we can go back to 1500 years ago, and try together to trace back how it used to look the topography of the city at the times of Theodoric and Justinian.

Becoming a capital…

The good fortune of the city was undoubtedly linked to the transfer of the capital of the Western Roman Empire from Milan to Ravenna. We’re talking about 402-403 AD.

Honorius, second to last western emperor, was afraid of the barbaric pressure coming from the Alps; for this reason, he decided to move all his dignitaries and officials to Romagna.

Away from the Via Emilia and the main communication routes (except for the Via Popilia), in this area marked by lagoons and brackish waters, hard to be reached by any possible enemies, feeling finally safe, he founded a steady government.

The city underwent a massive change. From a little Roman centre, it suddenly developed, turning into a capital. Hence, the new challenge was to equip it with a number of infrastructures that measured up the city’s new institutional role.

A changing city

First of all, the urban walls were extended: in little time the surface of the city grew from 33 to 166 ha. Despite the passing of centuries and the subsequent renovation works, you can still see some of the original walls: just walk along Via Porta Aurea or cross Piazzale Torre Umbriatica and you’ll see them.

Furthermore, the city was enhanced with new roads, some of which built from already existing paths. One above all deserves a mention: the huge porticoed road (today the central Via Mariani), discovered during the diggings at the beginning of the 21st century, connected the area of Ravenna Cathedral with the area of the imperial palace, which today corresponds to the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo.

Even the waterways became and still are a fundamental aspect of the area: the river and torrent Padenna met right in the heart of the city centre, at the height of the area that today hosts the city’s indoor market (Mercato Coperto). There were even two canals, one was Fossa Lamises and the other Fossa Augusta, which connected the city to the Venetian lagoon and presumably flew near the current Via di Roma.

Between the 5th and the 6th century, Ravenna lived a real rebirth in the local construction industry, featuring imposing public buildings, huge domus and infrastructures. All this expansion meant to answer the peculiar needs of the court and the emperor, and subsequently, of the Gothic masters, the exarch and bishops.

Religion in the time of Theoderic

The urban development was further enhanced by the spread of the Christian faith, which was almost unknown before the arrival of the emperor, and that saw many ecclesiastic authorities carve out some spaces for themselves in the city. An example is the Neonian Baptistery, Unesco monument built towards the first half of the 5th century.

The city started in this way to feature two focus points: on the one side the religious pole, rising around the bishop’s palace (which is still available, you just need to visit the Chapel of Sant’Andrea); on the other was the city pole, gravitating around the imperial palace.

These two poles were sided by a third one: as a matter of fact, at the end of the 5th century, Theodoric brought with him his folk of Arian religion, which started to live in an area without buildings located at the edges of the city that today is identified by the Arian Baptistery and the Church of Santo Spirito.

The great imperial palace

The most important element of the transformation of Ravenna’s urban texture remains the construction of a majestic imperial palace that didn’t survive to the present day.

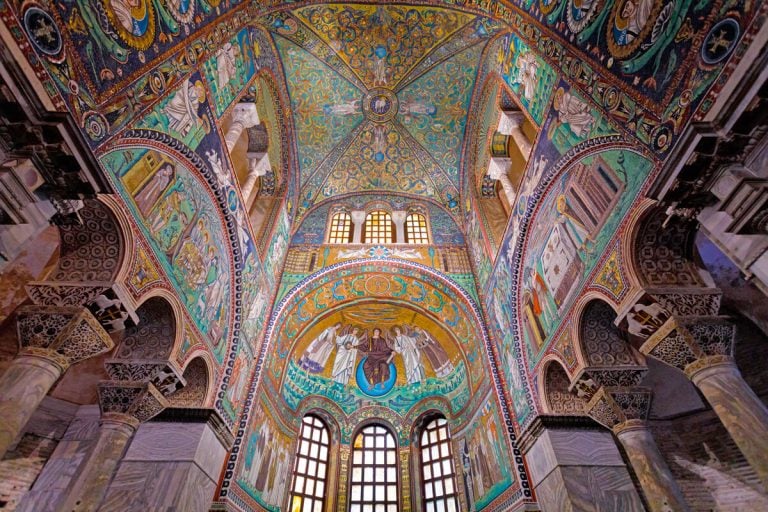

The only things left that prove its existence are the different types of material, discovered during some archaeological diggings at the beginning of the 20th century, and the depictions in the mosaics inside the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo.

This was not the only existing building, but it was just one part of a bigger complex of rooms that covered that wide-area comprised today between the Church of San Giovanni Evangelista and the Church of Santa Maria in Porto.

Among the several rooms, the complex also hosted a room dedicated to the soldier’s lodgings stationing at the palace, the Palatin Chapel (today Basilica of San’Apollinare Nuovo), the “Moneta Aurea” (site of the royal mint) and the circus, which might be recalled by the current similar-sounding toponym “Via Cerchio”.

If you want to find some hints of the presence of this complex, you can visit the (so-called) Palace of Theodoric. Even if it is actually a more recent building, dating back to the Carolingian epoch, it was probably built over the foundations of the Palace, as some of the mosaics discovered inside prove.

The development of private and religious construction

The economic growth and the increasing number of investments between the 5th and 7th century encouraged a new life to private construction industry. Some important archaeological diggings brought to light some buildings for residential use.

The most important example was the Domus of the Stone Carpets, a site you can still visit, located in the historical centre of the city.

It features a sequence of prestigious houses of Augustan age, all incorporated in one big dwelling, maybe belonged to a high dignitary of the imperial court, used even later in Byzantine times.

The buildings that mostly affected the landscape of the city between the 5th and 6th century, though, were without any doubts the churches.

It’s thanks to the construction of places of worship that Ravenna gained a monumental profile of the highest level, worthy of its role as the royal seat.

Not counting the cathedral, which had been the only church built before the transfer of the imperial court, at the beginning of the 5th century, the city saw a rather quick succession of new buildings rising, among which―just to mention some of the most important you can still visit Santa Croce and the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, San Giovanni Evangelista, the Church of Sant’Agata and the Basilica Apostolorum, now Basilica of San Francesco, with its flooded crypt and original mosaics dating back to the 5th century.

The same policy of improvements continued even during Theodoric’s rule (493-526AD), building in this period the Church of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, the Church of San Teodoro (later named Santo Spirito), along with the “Ecclesia Gothorum”, a building from which were presumably taken the capitals with the initials of the king written on it that today embellish the Venetian Loggetta in Piazza del Popolo.

The fervent activity of the Gothic king was sided by the works asked by the Episcopal circles. The most important businesses were recorded during the bishopric of Agnello and Maximianus (second half of the 5th century), supported of course by the financier Julian l’Argentario.

Despite all the political changes, this was maybe the most prosperous period for the city, during which was also ended the Basilica of San Vitale, undoubtedly one of the most prestigious buildings of late Antiquity and the little Church of San Michele in Africisco, today house to a famous boutique of the city centre, whose mosaic decoration is preserved inside the Bode Museum in Berlin. Lastly, during these years, was also built the imposing Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe.

The great commercial port of Ravenna

The great Port of the city flourished, right there, near the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe, founded at the beginning of the 5th century, when the capital was transferred.

The suburb of Classe became Ravenna’s entrance door to the Mediterranean, as the mosaics in the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo prove.

From there, millions of goods and foodstuff were shipped and delivered, connecting Ravenna to the Aegean area, Asia Minor and Palestine. It became a crossroad of people, objects and knowledge, all well explained in the Classis Museum, in the Classe Archaeological Park and in the collections of the National Museum in Ravenna.

The museum is part of the Archaeological Park of Classe, which awaits tourists and citizens, ready to tell the history of a city and its territory across the centuries that preceded the Middle Ages.

Author

Davide Marino

Davide Marino was born archaeologist but ended up doing other things. Rational – but not methodic, slow – but passionate. A young enthusiast with grey hair

You may also like

Discover Ravenna (Emilia-Romagna, Italy): Best Things to Do in the city

by Davide Marino /// November 16, 2017

Classis: a New Archaeological Museum For Ravenna

by Davide Marino /// November 22, 2018

The archaeological sites of Romagna

by Davide Marino /// February 9, 2018

Interested in our newsletter?

Every first of the month, an email (in Italian) with selected contents and upcoming events.

The Most Beautiful Churches and Cathedrals in Emilia-Romagna

by Davide Marino /// September 20, 2018

Via Emilia. History and origins of a region in 10 points

by Davide Marino /// June 29, 2018